Lm. GB. Nguyễn Đăng Trực, OP.

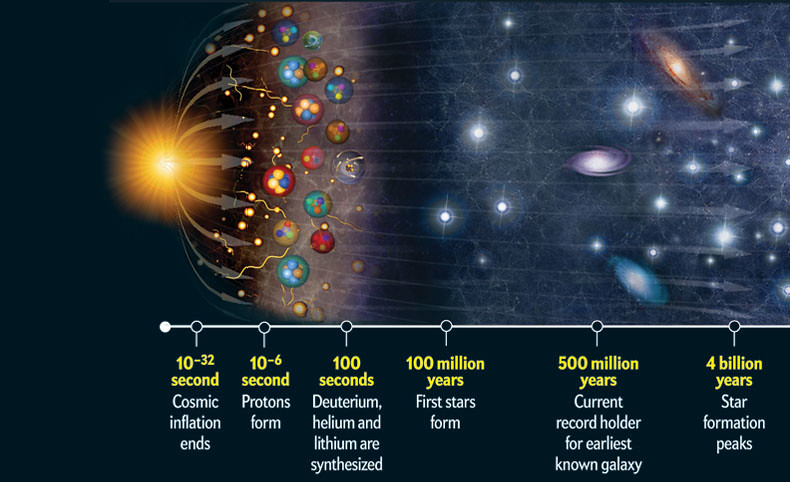

Phần lớn các nhà vật lý hiện đại đều cho rằng cách nay 15 tỉ năm, tài sản duy nhất của vũ trụ được gom tụ tại một điểm chấm vô cùng nhỏ bé, có mật độ vô hạn (vô cùng đặc) và một năng lượng cực cao. Rồi nó nổ tung, gọi là Big Bang (vụ nổ lớn). Một quá trình giãn nở diễn ra cực nhanh, các nhà vật lý thiên văn gọi là sự lạm phát (inflation). Tiếp đến là quá trình nguội dần, tạo điều kiện cho sự cấu tạo các nguyên tử, sau đó là sự ngưng tụ thành các giải ngân hà. 10 tỷ năm sau hình thành các hành tinh. Trái đất được hình thành cách nay khoảng 4 tỷ rưỡi năm. Các điều kiện thuận lợi cho sự sống xuất hiện.

Phần lớn các nhà vật lý hiện đại đều cho rằng cách nay 15 tỉ năm, tài sản duy nhất của vũ trụ được gom tụ tại một điểm chấm vô cùng nhỏ bé, có mật độ vô hạn (vô cùng đặc) và một năng lượng cực cao. Rồi nó nổ tung, gọi là Big Bang (vụ nổ lớn). Một quá trình giãn nở diễn ra cực nhanh, các nhà vật lý thiên văn gọi là sự lạm phát (inflation). Tiếp đến là quá trình nguội dần, tạo điều kiện cho sự cấu tạo các nguyên tử, sau đó là sự ngưng tụ thành các giải ngân hà. 10 tỷ năm sau hình thành các hành tinh. Trái đất được hình thành cách nay khoảng 4 tỷ rưỡi năm. Các điều kiện thuận lợi cho sự sống xuất hiện.

Rồi người ta tự hỏi: Cái gì đã gây nên vụ nổ lớn (Big Bang)? Ở thời điểm cực nhỏ 10-43 giây (sau vụ nổ), người ta gọi là thời gian Planck, hay bức tường Planck (tên một nhà vật lý người Đức), vật lý như chúng ta đã biết, mới xuất hiện cùng với không – thời gian.

Đằng sau bức tường Planck vẫn che dấu một hiện thực mà các nhà vật lý học chưa biết. Một số người cho rằng ở đó cặp không gian và thời gian vốn gắn bó với nhau rất chặt chẽ trong thế giới của chúng ta bị phá vỡ. Thời gian không tồn tại. Các khái niệm trước sau không có ý nghĩa gì. Vật lý mà chúng ta biết như ngày nay không thể đứng vững được. Vậy cái gì đã gây nên vụ nổ? Big Bang có phải là nguồn gốc (origin) của vũ trụ hay chỉ là khởi điểm (beginning) của vũ trụ?

I. NHỮNG GIẢ THIẾT KHOA HỌC VỀ NGUỒN GỐC BIG-BANG

Một số nhà vật lý đưa ra lý thuyết giải thích vụ nổ Big Bang là kết quả của sự “dao động chân không nguyên thủy” (fluctuation of a primal vacuum), tương tự hiện tượng các hạt hạ nguyên tử (sub-atomic particles) xuất hiện tự phát trong môi trường chân không trong các phòng thí nghiệm. Hay có người cho nó là kết quả của cái được gọi là “hiệu ứng xuyên hầm lượng tử từ hư không” (quantum tunneling from nothing). Toàn thể vũ trụ cũng ví tựa như những hiện tượng đó. Chúng ta đang sống trong một vũ trụ không cần một giải thích nào vượt lên chính nó, nghĩa là từ bên ngoài. Đó là một vũ trụ xuất hiện tự phát từ một hư không vũ trụ (cosmic nothingness). “Chúng ta tới từ hư không, bởi hư không, và cho hư không”. Vũ trụ hiện hữu cách tình cờ, ngẫu nhiên, không nguyên nhân. Nó hiện hữu tuyệt đối không một chút lý do (Atheism and Big Bang cosmology, William Craig and Quentin Smith, Oxford, 1993).

Một số nhà vật lý đưa ra lý thuyết giải thích vụ nổ Big Bang là kết quả của sự “dao động chân không nguyên thủy” (fluctuation of a primal vacuum), tương tự hiện tượng các hạt hạ nguyên tử (sub-atomic particles) xuất hiện tự phát trong môi trường chân không trong các phòng thí nghiệm. Hay có người cho nó là kết quả của cái được gọi là “hiệu ứng xuyên hầm lượng tử từ hư không” (quantum tunneling from nothing). Toàn thể vũ trụ cũng ví tựa như những hiện tượng đó. Chúng ta đang sống trong một vũ trụ không cần một giải thích nào vượt lên chính nó, nghĩa là từ bên ngoài. Đó là một vũ trụ xuất hiện tự phát từ một hư không vũ trụ (cosmic nothingness). “Chúng ta tới từ hư không, bởi hư không, và cho hư không”. Vũ trụ hiện hữu cách tình cờ, ngẫu nhiên, không nguyên nhân. Nó hiện hữu tuyệt đối không một chút lý do (Atheism and Big Bang cosmology, William Craig and Quentin Smith, Oxford, 1993).

Đối với Paul Davies, một nhà vật lý của Đại học Newcastle, trong “God and the new physics” (New York, 1983), vũ trụ xuất phát từ vụ nổ nguyên thủy là hiển nhiên. Ông luôn luôn dùng danh từ “tạo dựng” để chỉ về vụ nổ ấy, nhưng cuộc tạo dựng này lại không cần đến một đấng tạo hóa. Vì theo ông, cả vật chất lẫn năng lượng cũng như không gian và thời gian đều đã có thể xuất hiện tự phát, không cần đến một nguyên nhân nào. Đó chỉ là thành quả của “sự chuyển tiếp lượng tử không nguyên do” (causeless quantum trasition), nghĩa là có khả năng phát sinh ra những hạt cơ bản từ bởi không không. Toàn thể vũ trụ phát sinh từ bởi không không, tuyệt đối theo đúng những định luật vật lý lượng tử và trên đường tiến phát đã tạo nên tất cả vật chất cùng năng lượng cần cho việc kiến tạo thế giới mà chúng ta hiện đang thấy. Như vậy thế giới mang trong mình lời giải thích về chính mình.

II. NHẬN ĐỊNH

Nếu trở lại với sự phân biệt của Thánh Toma giữa quan niệm sáng tạo và sự đổi thay, thì toàn thể vũ trụ dù ở dưới dạng thức nào cũng là những sự vật đổi thay. Có đổi thay tất phải có chủ thể đổi thay. Do đó các “hiệu ứng xuyên hầm lượng tử từ hư vô” hay “dao động chân không lượng tử nguyên thủy” không thể phát xuất từ hư vô tuyệt đối. Dù chân không là vô hình tượng, không giống như bất cứ sự vật nào trong vũ trụ hiện nay của chúng ta, nhưng nó vẫn là một cái gì. Nó là chủ thể của sự “dao động”? Như vậy cái hư vô, hư không đó không trống rỗng tuyệt đối nhưng có chứa đựng một cái gì đó. Đã là cái gì đó, tất phải có thực thể khách quan. Thực thể khách quan ấy từ đâu mà có? Đây lại là vấn đề của siêu hình học chứ không phải của vật lý học.

Nếu trở lại với sự phân biệt của Thánh Toma giữa quan niệm sáng tạo và sự đổi thay, thì toàn thể vũ trụ dù ở dưới dạng thức nào cũng là những sự vật đổi thay. Có đổi thay tất phải có chủ thể đổi thay. Do đó các “hiệu ứng xuyên hầm lượng tử từ hư vô” hay “dao động chân không lượng tử nguyên thủy” không thể phát xuất từ hư vô tuyệt đối. Dù chân không là vô hình tượng, không giống như bất cứ sự vật nào trong vũ trụ hiện nay của chúng ta, nhưng nó vẫn là một cái gì. Nó là chủ thể của sự “dao động”? Như vậy cái hư vô, hư không đó không trống rỗng tuyệt đối nhưng có chứa đựng một cái gì đó. Đã là cái gì đó, tất phải có thực thể khách quan. Thực thể khách quan ấy từ đâu mà có? Đây lại là vấn đề của siêu hình học chứ không phải của vật lý học.

Vì thế Stephen Bar, một nhà vật lý học đã đưa ra một so sánh cho thấy cái thiếu sót trong luận chứng trên đây: không thể lẫn lộn giữa một trương mục ngân hàng trong đó không còn một xu nào với không có một trương mục ngân hàng nào hết. Có một trương mục ngân hàng dù không còn đồng xu nào trong đó vẫn ngấm ngầm đòi phải có một ngân hàng, một hợp đồng với ngân hàng đó, một hệ thống tiền tệ, một bản vị tiền tệ và luật ngân hàng… Những hạn từ “dao động lượng tử” hay “hiệu ứng xuyên hầm lượng tử” phải được áp dụng trong một tổng thể hệ thống với những luật lệ của nó chứ không thể áp dụng một cách tùy tiện. Thực tế cái hư không của các nhà vật lý đang nói đây là cái hư không trong khuôn khổ các định luật vật lý (nothing plus the laws of physics) và cái hư không trong chân không lượng tử (nothing plus the quantum vacuum) như chính ngôn ngữ nhà vật lý Paul Davies sử dụng.

Ngày nay, được xem là nhà vật lý lý thuyết lỗi lạc nhất là Stephen Hawking với cuốn “lược sử thời gian” (a brief history of time) trong đó ông đề xuất một kiểu mẫu vũ trụ làm sao để khỏi cần viện đến hành động sáng tạo của Thiên Chúa. Ông viết “khả năng không – thời gian là hữu hạn, song không có biên, điều đó có nghĩa là không có cái ban đầu, không có thời điểm của sáng tạo” (p.172). “Nếu mà vũ trụ có một điểm xuất phát, chúng ta buộc lòng phải giả định có một Đấng sáng tạo. Nhưng nếu vũ trụ là hoàn toàn tự thân, không biên không mút thì vũ trụ cũng không có bắt đầu, không có kết thúc” vũ trụ chỉ tồn tại. Vậy thì Đấng sáng tạo giữ vị trí gì đây? (p.205) Và trong lời giới thiệu, Carl Sagan cũng đồng quan điểm: “Vũ trụ không có biên trong không gian, không có bắt đầu và kết thúc trong thời gian và chẳng có việc gì cho Đấng sáng thế phải làm ở đây cả” (p.11).

Ngày nay, được xem là nhà vật lý lý thuyết lỗi lạc nhất là Stephen Hawking với cuốn “lược sử thời gian” (a brief history of time) trong đó ông đề xuất một kiểu mẫu vũ trụ làm sao để khỏi cần viện đến hành động sáng tạo của Thiên Chúa. Ông viết “khả năng không – thời gian là hữu hạn, song không có biên, điều đó có nghĩa là không có cái ban đầu, không có thời điểm của sáng tạo” (p.172). “Nếu mà vũ trụ có một điểm xuất phát, chúng ta buộc lòng phải giả định có một Đấng sáng tạo. Nhưng nếu vũ trụ là hoàn toàn tự thân, không biên không mút thì vũ trụ cũng không có bắt đầu, không có kết thúc” vũ trụ chỉ tồn tại. Vậy thì Đấng sáng tạo giữ vị trí gì đây? (p.205) Và trong lời giới thiệu, Carl Sagan cũng đồng quan điểm: “Vũ trụ không có biên trong không gian, không có bắt đầu và kết thúc trong thời gian và chẳng có việc gì cho Đấng sáng thế phải làm ở đây cả” (p.11).

Ý các ông muốn nói Big Bang là biến cố đánh dấu không những nguồn gốc vũ trụ nhưng còn là khởi đầu của thời gian. Không có thời gian trước Big Bang. Do đó Big Bang không có nguyên nhân vì nguyên nhân phải đi trước hiệu quả. Không có thời gian thì không có khái niệm trước sau thì cái gọi là nguyên nhân trở thành vô nghĩa. Còn chỗ nào cho Đấng sáng tạo?

Đối với Hawking cũng không có không gian ngoài Big Bang. Big Bang không giống như những vụ nổ khác, nghĩa là nó không diễn ra trong một không gian nhất định. Russell Stennard, giáo sư vật lý dùng một hình ảnh để minh họa: lấy một bong bóng cao su chưa bơm hơi, ta gắn vài hình tròn nhỏ lên đó. Những hình đó tượng trưng cho các ngân hà (galaxies). Bây giờ hãy bơm hơi vào bong bóng. Nó giãn nở ra. Ta thấy các hình tròn nhỏ di chuyển càng lúc càng xa nhau. Theo đó, các nhà vật lý giải thích trong vụ nổ Big Bang, các ngân hà không di chuyển qua một không gian có sẵn. Đúng hơn, không gian giữa các ngân hà đang giãn nở ra. Như vậy không có không gian ba chiều trống rỗng bên ngoài các ngân hà mà chúng ta quan sát được. Các nhà vật lý kết luận: ở khoảnh khắc vụ nổ Big Bang, không gian chúng ta quan sát được như ngày nay bị nén lại thành một điểm vô cùng nhỏ. Do đó Big Bang không chỉ nói lên nguồn gốc vũ trụ nhưng còn khẳng định sự xuất hiện của không gian. Không có không gian bên ngoài Big Bang. Không gian phát sinh từ không không và tiếp tục tiến phát từ đó, cách tự thân, tự phát.

III. PHÊ BÌNH

Thánh Âutinh sống cách chúng ta khoảng 1500 năm, ngài không có một khái niệm nào về vụ nổ Big Bang, nhưng ngài đã nói về vấn đề thời gian như sau: tìm kiếm thời gian trước cuộc Sáng tạo là một việc làm vô ích. Làm như thế có khác gì tìm kiếm thời gian trước thời gian. Nếu không có sự vật chuyển dịch, chúng ta không thể phân biệt thời điểm này với thời điểm khác. Nếu không có sự vật đang chuyển dịch hay ở thế bất động (vì chúng chưa được sáng tạo) thì thời gian chỉ là khái niệm vô nghĩa và trống rỗng. Như vậy thời gian khởi đầu với sáng tạo hơn là sáng tạo khởi đầu với thời gian. Thánh Âu Tinh đã khéo léo cho rằng thời gian cũng được sáng tạo như những thụ tạo khác. Và như vậy, không có thời gian trước sáng tạo cũng không ảnh hưởng trái nghịch với niềm tin tôn giáo (God and the Big Bang, Russell Stannard, Tablet, 2000).

Thánh Âutinh sống cách chúng ta khoảng 1500 năm, ngài không có một khái niệm nào về vụ nổ Big Bang, nhưng ngài đã nói về vấn đề thời gian như sau: tìm kiếm thời gian trước cuộc Sáng tạo là một việc làm vô ích. Làm như thế có khác gì tìm kiếm thời gian trước thời gian. Nếu không có sự vật chuyển dịch, chúng ta không thể phân biệt thời điểm này với thời điểm khác. Nếu không có sự vật đang chuyển dịch hay ở thế bất động (vì chúng chưa được sáng tạo) thì thời gian chỉ là khái niệm vô nghĩa và trống rỗng. Như vậy thời gian khởi đầu với sáng tạo hơn là sáng tạo khởi đầu với thời gian. Thánh Âu Tinh đã khéo léo cho rằng thời gian cũng được sáng tạo như những thụ tạo khác. Và như vậy, không có thời gian trước sáng tạo cũng không ảnh hưởng trái nghịch với niềm tin tôn giáo (God and the Big Bang, Russell Stannard, Tablet, 2000).

Hơn nữa, đối với Hawking, nguyên nhân và hậu quả là những khái niệm thuộc thời gian, từ đó ông diễn dịch ra rằng vì trước Big Bang đã không có thời gian nên cũng không có một nguyên nhân cho chính Big Bang ấy.

Như đã nghiên cứu ở tiết trước, đối với thánh Toma, nguyên nhân và hậu quả trước tiên là những khái niệm thuộc về hữu thể rồi sau đó mới là những khái niệm thuộc thời gian và tính cách ưu tiên hữu thể của nguyên nhân đối với hậu quả không nhất thiết đòi phải có tính cách ưu tiên về phương diện thời gian. Theo quan điểm của ngài về sự sáng tạo thì sáng tạo chủ yếu không phải là một sự khai mào xét về phương diện thời gian mà hệ tại ở mối tương quan lệ thuộc về hữu thể. Do đó ngài không ngần ngại khẳng định vũ trụ có thể được sáng tạo từ đời đời.

Thực ra, qua các văn kiện, Giáo hội rất trân trọng các nhà khoa học và những thành quả họ đã cống hiến cho nhân loại, trong đó có Hawking, một nhà vật lý được thế giới ngưỡng mộ. Nhưng trong “lịch sử thời gian” ông có khuynh hướng của chủ nghĩa thuyết giản lược (reductionism) thu gọn mọi chân lý thực tại vào lãnh vực khoa học vật lý, dẫn đến thái độ phủ nhận sự hiện hữu và những hoạt động của thực tại tối hậu Sáng tạo. Lại nữa, do kiến thức về siêu hình học còn giới hạn nên ông đưa ra những khẳng định còn hạn chế như không phân biệt rạch ròi thực tại tất yếu hay tất hữu với những thực tại bất tất nên ông đã tra vấn “Vũ trụ cần một Đấng sáng tạo… Vậy ai sáng tạo ra Đấng sáng tạo?” (p.263). Hay chính ông cũng thừa nhận vũ trụ được điều chỉnh một cách vô cùng chính xác, hài hòa, chỉ khác đi một chút thôi thì vũ trụ đã không tồn tại tới ngày nay và các sinh vật, trong đó có con người, đã không thể xuất hiện. Chính điều kì diệu này các nhà vật lý đã gọi là “nguyên lý vị nhân” (anthropic principle). Nhưng trước sự kỳ diệu này, Hawking chỉ đưa ra câu khẳng định quá giản đơn: “Nếu vũ trụ khác đi một chút thì chúng ta đã không ở đây” (p.184). Sự kiện chúng ta ở đây chẳng liên quan gì đến vấn đề đang thảo luận là vấn đề thuộc lãnh vực hiện hữu hay siêu hình học. Vấn đề là: Tại sao chúng ta ở đây? Tại sao lại có cái gì đó chứ không phải là không có cái gì? Vấn đề này khoa học không thể trả lời được. Vì cái không gì cả đơn giản hơn và dễ hơn cái gì đó.

Đó chính là vấn đề uyên nguyên của hiện hữu mà thánh Toma kiếm tìm trong “Ngũ đạo” của ngài.

———-

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

PHỤ LỤC

By John F. X. Knasas

I want to discuss the place of Fides et Ratio within the parameters of the 20th century Thomistic revival. To do that I must first describe the revival. Three strains of Thomistic interpretation characterized the revival before Vatical II: Aristotelian Thomism, Exitential Thomism and Transcendental Thomism. The first two were a posteriori in their epistemology.i The mind abstractly draws its fundamental conceptual content from the human knower’s contact with the seft-manifestly real things given in secsation. Among the concepts abstracted are the transcendentals, chief among which is the ratio entis, the notion or concept of being. It is an analogical commonality, and so a sameness within difference, whose analogates are absolutely everything, action and conceivable. ii

Aristotelian Thomists and Existential Thomists dispute among themselves about the precise definition of being. The Aristotelian Thomists say that a being basically is a possessor of format act (forma). This thinking derives from their central use of Aristotle’s hylomorphic analysis of changeable sensible substance. What impresses these Thomists is the definiteness and determinateness of sensible things. These aspects are rooted in the substantial from of a things that is understood to be caused in matter by a moving agent. Ultimately this moving agents is an unmoved mover that is, in their opinion, identifiable with the Christian God.iii

Most famous of the Existential Thomists were Etienne Gilson and Jacques Maritain. They proposed a more fudandamental description of being in terms of existential act. iv The Existential Thomists use that they regard as Aquinas’ philosophically novel doctrine of esse, or actus essendi. v The “existence of a thing” does mot mean simply the fact of the thing, though ordinary conversation does leave it at that. Philosophical reflection discerns that the thing’s existence is an act of the thing somewhat similarly as a man’s running and speaking are other acts, though existential act is unique in its basicness and fundamentality to the thing. In creatures, the act of existing is participated; in the Creator it is subsistent. Such a first cause is identifiable with the God of JudeoChristian revelation, who in the Vulgate told Moses that his name was “Ego sum qui sum.”

Despite this disagreement both camps agree on the mind’s ability to work out in a posteriori fashion transcendental concepts, i. e., analogous commonalities that apply to absolutely everything. Hence, both camps are of the opinion that in principle, if not in fact, a single fundamental science of the real exists. No matter where or when one lives, the real beings before him in sensation are sufficient for the human intellect to work out a posteriori the analogous concept of being and to correctly read its nature. Consequently, if metaphysics is expressive of the crowning natural achievement of the human mind, then obviously theology must be done in term s of this one, true theology exists. From the vantage point of these two camps, it is not possible to have great metaphysics and great theologies that are all true, just as it is possible to have varied great athletes that are all genuine. If they are worthy of their name, various metaphysics bear on the transcendental of being, and they do this adequately or not.

The third strain of 20th century Thomistic interpretation is Transcendental Thomism. If follows a different epistemology than the others. vi At its most fundamental level, human knowing involves not reception from the real but a projection of the knower upon the real. The knower’s projection is the knower’s own intellectual dynamism to the unconceptualizable term of Infinite Being. Hence, the intellect’s basic contact with reality is not through concepts abstracted from things, as is the case in the previous two camps. Rather, the intellect’s contact is through its own dynamism to Infinite Being. In the life of the mind, prior to static concepts is intellectual dynamism.

Intellectual dynamism is not only innate, or a priori. It is also “constitutive” of human awareness. Thanks to its immersion in the dynamism, the data of sense can profile itself in consciousness as finite and limited in perfection. A refrain among Transcendental Thomists is: “You can know the finite only if you know the infinite; you can know the limited only if you know the unlimited.” vii Both the finite and the limited appear only in juxtaposition to the infinite and unlimited. The intellect’s dynamism to Infinite Being is what sets up that juxtaposition. As so held before consciousness, the data permits the abstraction of analogous concepts as described in the traditional Thomist account of knowledge and repeated by Aristotelian and Existential Thomists. But for Transcendental Thomists that traditional account is by itself insufficient. It fails to explain the initial setting up of the sense data as the finite being that they are.

It is helpful to understand Transcendental Thomist epistemology in term of an extrapolation from visual experience. We see the outlines of things, things “objectify” themselves, only up and against something larger. For instance we see the frame only against the wall, and we see the Cathedral clock tower only against the sky. The wall and the sky are conditions for the perception of these objects. “Objectification” only happens in the light of something larger. Similarly, things are appreciated as finite beings, as realities not having all perfection, up and against something – Absolute Being, the term of intellectual dynamism. Intellectual dynamism places an “intellectual sky” against which things can profile themselves as beings of finite perfection.

The a posteriori Thomists will not dispute the facts but the Transcendental Thomist interpretation of them. In terms of his immediate realism for sensation, the a posteriori Thomist will understand the objectification of things as finite beings in terms of an automatic and natural abstraction of the ratio entis. Against the richness of that abstractum, things will appear as finite beings. No need exists to understand the intellectual backdrop as an a priori projection of the human knower. The Transcendental Thomist will be quick to reply that the immediate realism presumed by this abstractive account is just naive and dogmatic. Descartes’ dream and hallucination possibilities, and the relativity in perception hammered on by the empiricists explain why, since the modern period, no philosophers of note have espoused that the data of sensation is self-manifestly real.

Transcendental Thomism claims to be a more in depth presentation of the human knower than was achieved by Immanuel Kant. Hence, the name of this third camp. The Transcendental Thomists take exception to the metaphysical skepticism of Kant’s first Critique. Any doubts about the non-distortive character of intellectual dynamics are resolved by its ineluctability. Doubt about something presupposes the ability to envisage other possibilities. But since intellectual dynamism is constitutive of human consciousness, any doubt about it will employ it. Hence, the doubt destroys itself. Transcendental Thomism calls this defense of realism retorsion or performative self-contradiction. viii They find a basic for it in Aquinas’ commentary on

Aristotle’s defense of the non-contradiction principle at Metaphysics IV. Other Thomists are not impressed. ix

Because of its epistemology, Transcendental Thomism has a different relation than a posteriori Thomism to the undeniable fact of philosophical pluralism.x A posteriori Thomism claimed that despite the facts, in principle only one, true philosophy exists. This is because there is a single concept of being dor all men who are struggling to understand how to fundamentally describe it. Transcendental Thomists claim that in principle one, true philosophy cannot exist. Since all concepts form in the wake of intellectual dynamism, then no concept adequately catches the end of the dynamism. Hence, far from being in contradiction to each other, each great metaphysisc is a true but finite conceptual attempt to express the intellectual dynamism. Somewhat similarly each great athlete is a true but finite expression of the greatness that is common to all.

All tree currents streamed into Vatican II. But, as a matter of historical fact, only Transcendental Thomism emerged with any vibrancy. In the time since and especially in its use by theologians Karl Rahner, Henri de Lubac, and Bernard J. F. Lonergan, Transcendental Thomism has been the reigning Thomism. How does Fides et Ratio position itself with regard to these Thomistic camps? Of course, the dominant theme in the encyclical is the Pope’s plea to philosophers not to despair. The human mind has the ability to know absolute truth – truth that is certain and holding for all times and places (para. 27). A self-doubt exists among philosophers who since the Enlightenment have done their thinking independent of the Church. Ironically, it is now the Church that is encouraging philosophers. But what is striking is the “metaphysical” character of the Pope’s plea. By my count, the word “metaphysics”, or its equivalent “philosophy of being”, is mentioned at least 23 times. The Pope describes the desired metaphysics both in general and in particular. In general, he characterizes it in three ways. First, a phisolophy of genuinely metaphysical range transcends “… empirical data in order to attain something absolute, ultimate, and foundational in its search for truth” (Para. 83). This truth includes the truth of God’s existence. Second, language is regarded as having the capacity to express transcendent reality in statements “that are simply true”. Such statement involve “…certain basic concepts [that] retain their universal epistemological value and thus retain the truth of the propositions in which they are expressed” (Para. 96, also, n. 113). Third, earlier, the encyclical describes philosophical knowledge of God in a posteriori term. This knowledge begins from the creatures that are sensible things and reaches God as Creator. In other words, it reaches God in “causal” terms (Para. 19).

Event at this point the encyclical has to be a disappointment both to the Aristotelian and Transcendental Thomist. To philosophically reach God, the Aristotelian Thomist would use the proof from motion understood as an argument within natural philosophy, not metaphysics. The transcendental Thomist would disparage causal inquiry for the transcendental analysis of the a priori conditions of consciousness. Though the encyclical repeatedly speaks of the “wonder” that begins philosophy (Para. 4), the “stirring” and “ceaseless effort” of the human mind (Para. 14), “a seed of desire and nostalgia for God” in the “far reaches of the human heart” (Para. 24), the search for truth “so deeply rooted in human nature” (Para. 29), “the human being’s characteristic openness to the universal and the transcendent” (Para. 70), “the religious impulse innate in every person” (Para. 81), none of these descriptions correspond to what the Transcendental Thomist call the a priori intellectual dynamism. Rather, they all occur within the a posteriori context mentioned above. Sensible reality is what excites the mind and stirs it into causal inquiry that reaches God. The capacity of the mind to be excited in this way is what the encyclical means by the innate religious impulse.

These observations would lead one to correlate the encyclical with Existential Thomism. It is a posteriori and reserves knowledge of God to metaphysics. But the encyclical does the reader a favor by itself making the connection. While discussing the help that the intellectus fidei [the understanding of the faith, or theology] obtains from philosophy, the Pope emphasizes the value of a metaphysics, or philosophy of being, that is based on the very act of being:

If the intellectus fidei wishes to integrate all the wealth of the theological tradition, it must turn to the philosophy of being, which should be able to propose anew the problem of being – and this in harmony with the demands and insights of the entire philosophical tradition, including philosophy of more recent times, without lapsing into sterile repetition of antiquated formula. Set within the Christian metaphysical tradition, the philosophy of being is a dynamic philosophy that views reality in its ontological, causal and communicative structures. It is strong and enduring because it is based upon the very act of being itself, which allows a full and comprehensive openness to reality as a whole, surpassing every limit in order to reach the One who brings all things to fulfillment (115). In theology, which draws its principles from Revelation as a new source of knowledge, this perspective is confirmed by the intimate relationship which exists between faith and metaphysical reasoning (Para. 97).

What is this “philosophy of being based upon the act of being?” Affixed to the text quoted above is note 115. The note refers to the Pope’s 1979 Angelicum address on the centenary of Leo XIII’s encyclical Aeterni Patris. In reiterating the Church’s tradition of recommending Aquinas, Aeterni Patris conferred a decisive impetus to the 20th century revival of Thomism. The reference to the Angelicum address includes the following:

The philosophy of St. Thomas deserves to be attentively studied and accepted with conviction by the youth of our day by reason of its spirit of openness and of universalism, characteristics which are hard to find in many trends of contemporary thought. What is meant is an openness to the whole of reality in all its parts and dimensions, without either reducing reality or confining thought to particular forms or aspects (and without turning singular aspects into absolutes), as intelligence demands in the name of objective and integral truth about what is real. Such openness is also a significant and distinctive mark is its catholicity. The basic and source of this openness lie in the fact that the philosophy of St. Thomas is a philosophy of being, that is, of the “act of existing” (actus essendi) whose transcendental value paves the most direct way to rise to the knowledge of subsisting Being and pure Act, namely to God. On account of this we can even call this philosophy: the philosophy of the proclamation of being, a chant in praise of what exists. xi

No doubt should exist that Fides et Ratio is referring to Aquinas’ central metaphysical notion of actus essendi. Elaborating on actus essendi as the most direct way to rise to the knowledge of God, section 6 of the Angelicum address continues:…

It is by reason of this affirmation of being that the philosophy of St. Thomas is able to, and indeed must, go beyond all that presents itself directly in knowledge as an existing thing (given thorough experience) in other to reach “that which subsists as sheer Existing” (ipsum Esse subsistens) and also creative Love; for it is this which provides the ultimate (and therefore necessary) explanation of the fact that “it is preferable to be than not to be” (Potius est esse quam non esse) and, in particular, of the fact that we exist. “This existing itself”, Aquinas tells us, “is the most common effect of all, prior and more intimate than any other effect; that is why such an effect is due to a power that, of itself, belongs to God alone” (Ipsum enim esse est communissimus effectus, primus et intimior omnibus aliis effectibus; et ideo soli Deo competit secundum virtutem propriam talis effectus: QQ. DD. De Potentia, q. 3, a.7, c.)xii

Again, the Pope’s concern with the specific Thomistic doctrine of actus essendi, or esse, is patent. Through this actus essendi understanding of what is meant by the existence of a thing, Aquinas’ philosophy is so open to all of reality that the human intellect comes to know God.

Hence, of the various Thomistic camps in the 20th century Thomistic revival, the Pope’s clear preference is for the Existential Thomist camp. But from the encyclical itself, some objections to this specific Thomistic recommendation might be mounted. First, the Poe remarks, “The Church has no philosophy of her own nor does she canonize any one particular philosophy in preference to others.” (Para. 49). Does this remark contradict the specific recommendation of Aquinas’ actus essendi doctrine? Not necessarily. The remark does contradict the recommendation if the recommendation is treated as more than a recommendation. But by this first remark, the Pope makes it clear that the Church will never put its infallible seal of approval on any one particular philosophy. The wisdom of this approach is that the Church both encourages philosophers who may need encouragement and yet leaves philosophers free to disagree with each other. This approach assures that their mutual agreement will be attained by a particular doctrine making the philosophical case for itself.

Second, “… no historical form of philosophy can legitimately claim to embrace the totality of truth, nor to be the complete explanation of the human being, of the world, and of the human being’s relationship with God” (Para. 51). Why should this not include

Thomism? And so how could the Pope recommend Thomism as the metaphysics that is universally and absolutely true? This second remark should not include

Thomism for two reasons. First, as the previously cited Angelicum texts make clear, Aquinas’ philosophy of actus essendi does not claim to embrace the totality of truth but to be “open” to all truth. Second, the “historical forms of philosophy” are secular philosophies that proceed with a deaf ear to the faith. Christian philosophy, of which Thomism is a model example, follows a methodology in which faith prompts one’s thinking to the limits and so helps to avoid the limitedness of viewpoint and framework that is the bane of “historical”, i.e., secular, forms of philosophy.

Third, the encyclical notes “… the Magisterium has repeatedly acclaimed the merits of Saint Thomas’ thought and made him the guide and model for theological studies. This has not been in order to take a position on properly philosophical questions nor to demand adherence to particular theses” (Para. 78). How can this emark square with the up-a-head recommendation (Para. 97) of the actus essendi doctrine is being recommended only. There is no demanding adherence to it. Second, I want to note that this third remark is in the past tense. It describes what the Magisterium has done. But the next paragraph makes clear that the Pope intends to go beyond past recommending of Aquinas as a model for harmonizing faith and reason. With paragraph 97 to follow, the Pope remarks, “Developing further what the Magisterium before me has taught, I intend in this final section to point out certain requirements which theology… makes today of philosophical thinking and contemporary philosophies.”

Hence, among encyclicals enjoining intellectuals to study Aquinas, Fides et Ratio stands out for one reason. Though singling out Aquinas for strong Papal endorsement, previous encyclicals hardly, if ever, singled out specific points of Thomistic doctrine. Rather, they confined themselves to offering Aquinas as a general model, or an ideal case, of how Catholic intellectuals should strive to harmonize faith and reason. Intellectuals should try to do “the kind” of thing that Aquinas did, though not necessarily what he did. Hence, proponets of Teilhard de Chardin and of Liberation Theology in their attempts to harmonize faith and science of faith and politics could all claim to be following the recommendations of the Church to do “the kind” of thing done so exemplarily by Aquinas. Fides et Ratio breaks the mod of these past Papal encyclicals. John Paul II recommends the study of a specific point of Thomist doctrine. His clear preference and recommendation is that the actus essendi discovery of 20th century Thomistic scholarship and its development in Existential Thomism be not eclipsed from philosophical discussion at century’s end. In this manner Fides et Ratio continues the Thomistic Revival into the 21st century.

i Speaking of classical realism, Gilson, an Existential Thomist asks, “Is it so difficult, then, to understand that the concept of being is presented to knowledge as an intuitive perception since the being conceived is that of a sensible intuitively perceived? The existential acts which affect and impregnate the intellect through the senses are raised to the level of consciousness, and realist knowledge flows forth from this immediate contact between object and knowing subject”. Etienne Gilson, Thomist Realism and the Critique of Knowledge, trans. Mark A Wauck (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986), 206 and passim. Likewise, Maritain remarks, “… in the final reckoning, the primary basis for the veracity of our knowledge” is the “resolving of the sense’s knowledge into the thing itself and actual existence”. The Degrees of Knowledge, trans. By Gerald Phelan (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1959), 118, n.1; also Peasan,100; and Maritain’s many remarks on his “l’ intuition de l’être”. For the Aristoteli an Thomists (viz., the “River Forest” Dominicans – William Wallace) the a posteriori origin of knowledge is reflected in the methodological primacy of natural philosophy (Aristotelian physics) over metaphysics. Natural philosophy has ens mobile as its subject, viz., sensible things as changeable. For a description of this neo-Thomist camp, see Benedict Ashley, “The River Forest School and the Philosophy of Nature Today”, in Philosophy and the God of Abraham, ed. R. James Long (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1991), 1-16.

ii On Aquinas’ understanding of analogical conceptualization, see my “Aquinas, Analogy, and the Divine Infinity,: Doctor Communis, 40 (1987), 71-6.

iii See Ashley article cited supra n.1.

iv For Gilson, vd., God and Philosophy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964), 63, 65, 67, 70; Being and Some Philosophers (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1952), 5, 202, 214; The Elements of Christian Philosophy (New York: New American Library, 1963), 143. For Maritain, Existence and the Existent, trans. By L. Galantiere and G. B. Phelan (New York: Vintage Books, 1966), “The Concept of Existence or of To-exist (esse) and that of Being or of That-which-is (ens), 22-35.

v For the existental act understanding of being: “ Sicut autem motus est actus ipsius mobillis inquantum mobile est; ita esse est actus existentis, inquantum ens est.” (In I Sent., d.19, q.2, a.3c); “Nam ens dicitur quasi esse habens, …” (In XII Meta., lect. 1). Also, In I sent., d. 19, q.5, a. 1c; De Ver., I, 1, ad 3m, second set; S. C. G. II, 54; S. T. I, 44, 2c.

vi For a sympathetic description with references, see Joseph Donceel, “Transcendental Thomism”, The Monist, 58 (1974), 67-85. For a critical description with references, see my “Intellectual Dynamism in Transcendental Thomism; A Metathysical Assessment”, American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, 69 (1995), 15-28.

vii Whenever we think of a being, we can think of a greater being; in fact, we do so spontaneously, at least in this sense: that whenever we think of a being, we realize at once that this being is finite, limited. But – and this is a remark of utmost importance – In order to know a limit as limit, we must, in fact or in our striving be beyond that limit”. Joseph Donceel, Natural Theology (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1962), 20. Also, 59 and 66.

viii “This explains the great importance of ‘retorsion’ in Transcendental Thomism. ‘Retorsion’ is a technical term which refers to the method of demonstrating an assertion by showing that he who denies the assertion affirms it in his very denial”. Donceel, “Transcendental Thomism”, p.18. For Maréchal’s key exercise of retorsion, see Joseph Donceel, A Maréchal Reader, (New York: Herder and Herder, 1970), 215-17, 227-8; For Karl Rahner, “Aquinas: The Notion of Truth”, Continuum, 2 (1964), 69; for Bernard J. F. Lonergan, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding, (New York: Longmans, 1965), 352 on being as unrestricted.

ix See Knasas, “Intellectual Dynamism”, pp. 23-25.

x Gerald McCool, Catholic Theology in the Nineteenth Century: The Quest for a Unitary Method (New York: The Seabury Press, 1977), 257-9; From Unity to Pluralism: The Internal Evolution of Thomism (New York: Fordham University Press, 1992), ch. 9 but esp. 214-19.

xi John Paul II, “Perennial Philosophy of St. Thomas for the Youth of Our Times”, Angelicum, 57 (1980), 139-40.

xii Ibid., pp. 140-1.